Day 1: Compound Interest#

“The magic of compounding returns is the biggest mathematical discovery of all time.”

—Benjamin Graham (1894–1976), Economist and Investor

Compound interest is the financial law of slow, steady magic: you earn interest on your interest. That small difference can turn relatively small savings into substantial wealth over decades.

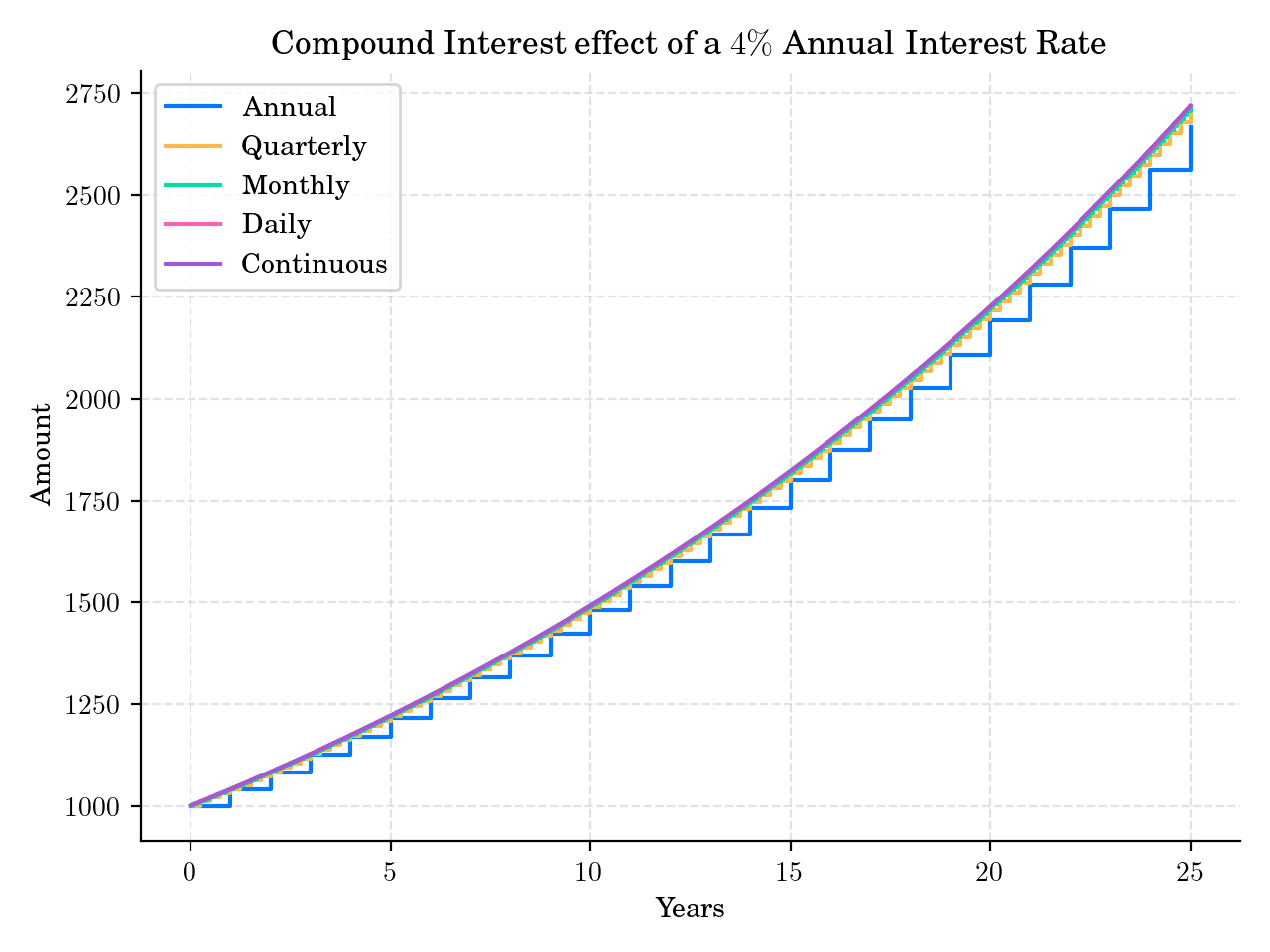

Definition. The total amount \(A\) after \(t\) years with discrete compounding over a principal \(P\) is given by

where

P: be the initial amount (principal),r: the annual nominal interest rate,n: the number of compounding periods per year,t: the time in years.

For example:

Annual compounding, i.e.

n = 1gives \(A = P(1 + r)^{t}\).Quarterly compounding, i.e.

n = 4gives \(A = P\left(1 + \frac{r}{4}\right)^{4t}\).

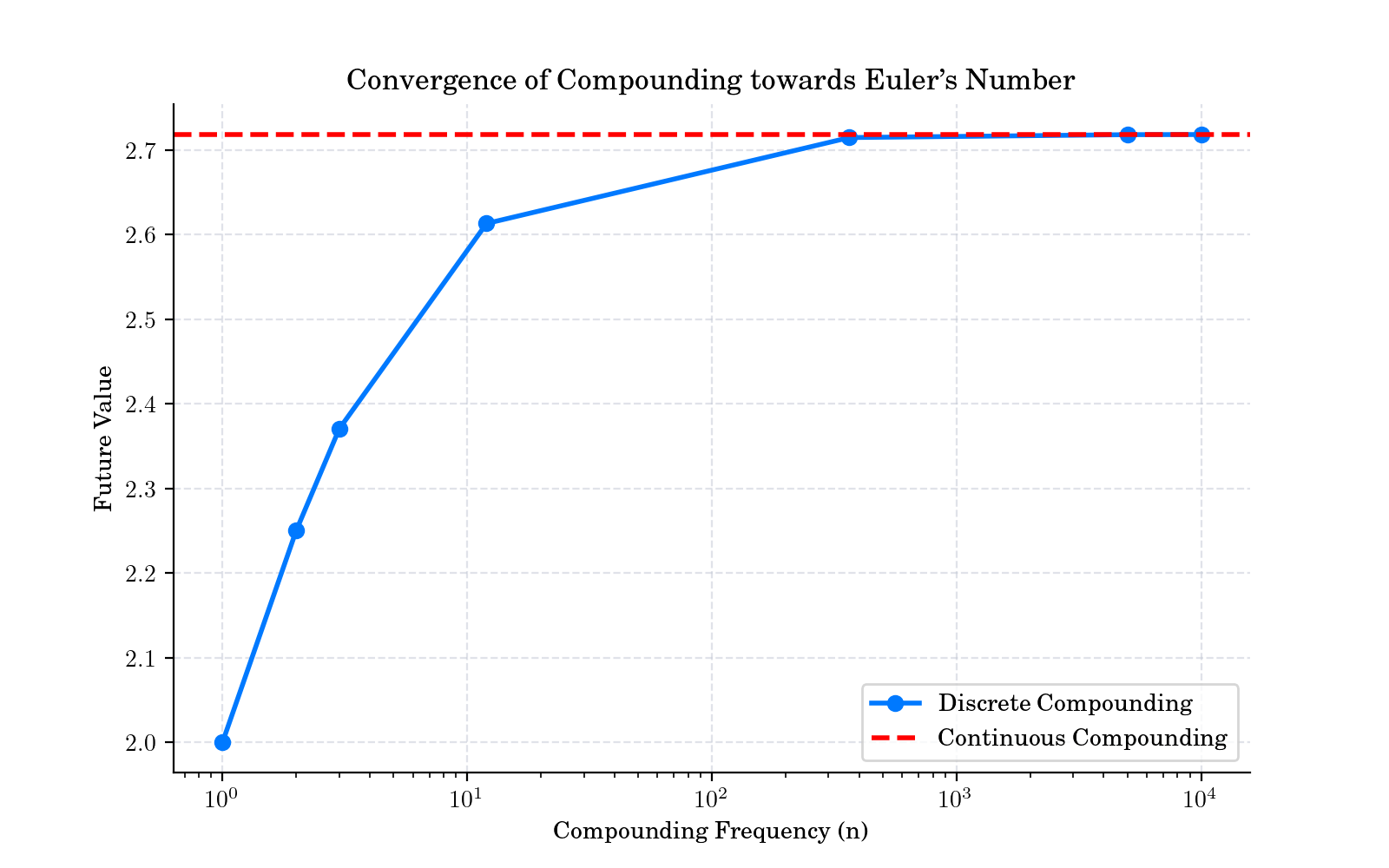

Taking the limit as \(n\) tends to infinity gives the formula for continuous compounding:

where \(e\) is Euler’s number (\(e \approx 2.71828\)).

Random Facts#

Compound Interest and the Euler’s number: The Euler’s number (or Napier’s constant) was actually introduced to solve the problem of continuous compounding of interest by Swiss mathematician Jacob Bernoulli in 1683. In his solution, the constant \(e\) occurs as the limit

\[\lim_{n\to \infty }\left(1+{\frac {1}{n}}\right)^{n} = e\]where \(n\) represents the number of intervals in a year on which the compound interest is evaluated.

The first symbol used for this constant was the letter b by Leibniz in letters to Christiaan Huygens in 1690 and 1691.

However, Leonhard Euler started to use \(e\) to denote the constant around 1728, in an unpublished paper on explosive forces in cannons, and in a letter to Christian Goldbach on 25 November 1731. The first appearance of \(e\) in a printed publication was in Euler’s Mechanica (1736), a two-volume work which describes analytically the mathematics governing movement.

A common rule of thumb is the Rule of 72: the doubling time (in years) is approximately \(72/(100r)\) when \(r\) is given as a percent (e.g. 4% → 72/4 = 18 years).

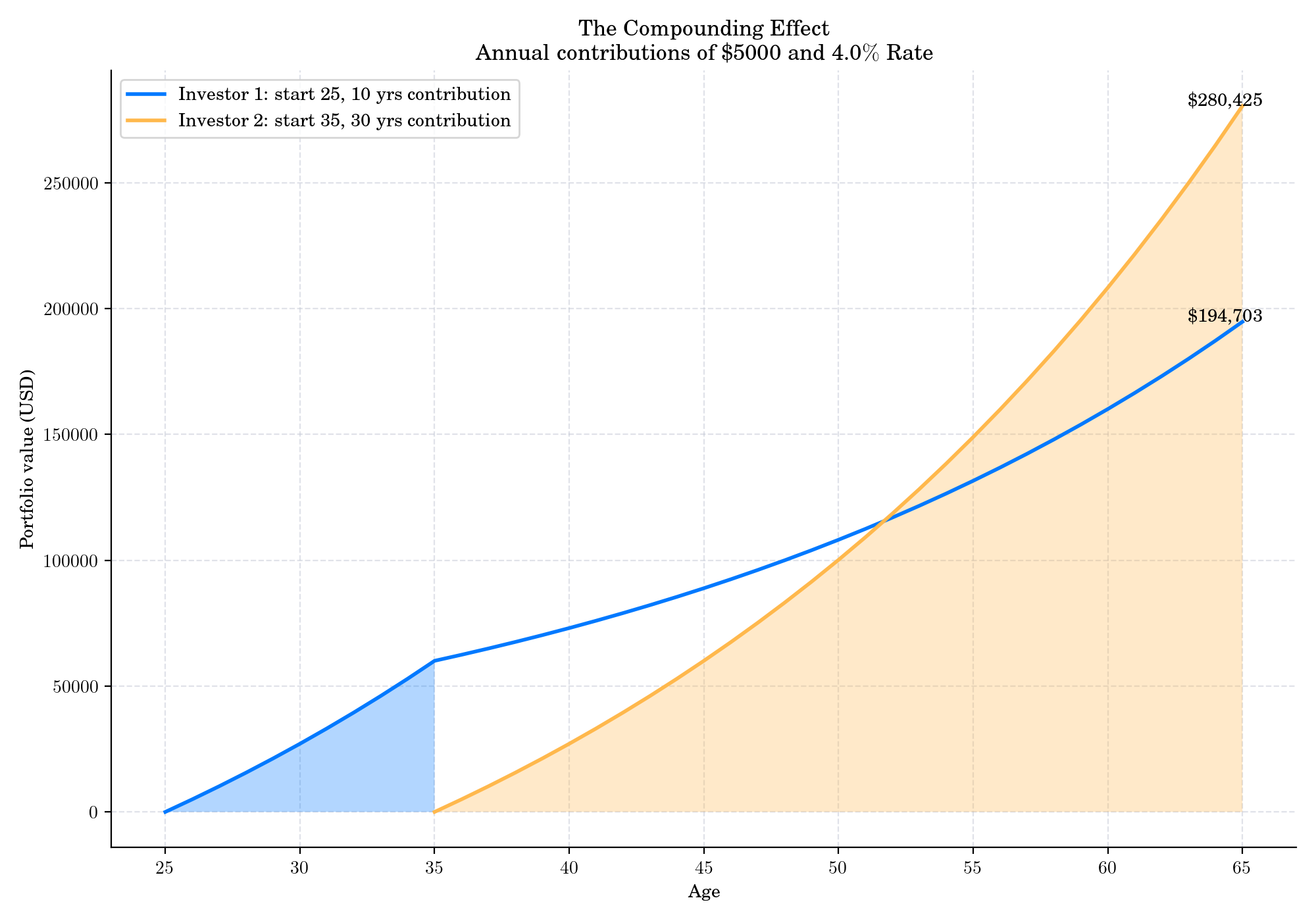

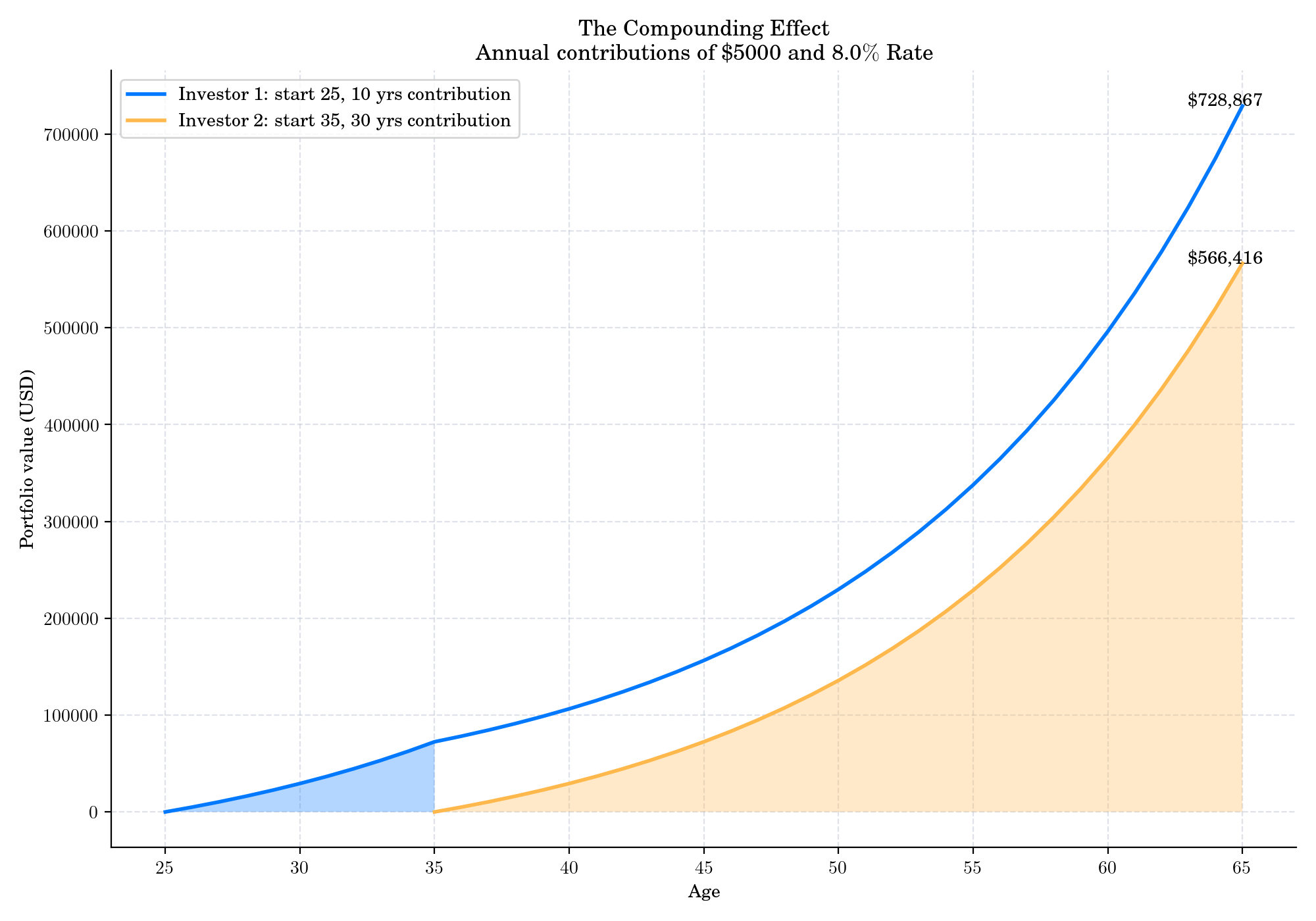

Power of starting early: If two people invest the same monthly amount but one starts 10 years earlier than the other, the earlier starter usually ends up with far more, even if they stop contributing earlier — thanks to compounding on larger balances. Start early, be consistent, and let time be your ally.

Even small amounts, given enough time, can grow in surprising ways.

But obviously, the interest rate is the key piece. Look at the same plot with a 4% rate instead of 8%.